In 1945, Ms. W. Whitby, a Black woman working in the Richmond shipyards as part of the war effort, came back from a trip to her mother’s to find the door to her war housing dormitory apartment padlocked shut. She had just separated from her husband and was planning to have her three children and mother come live with her.

Ms. Whitby was new to the dormitory. Not long before she moved in, the Richmond Housing Authority, who managed the apartments, had finally been forced by civil rights advocates to open its doors to Black women. Despite the order, the housing authority was intent on limiting the number of Black tenants, and where that failed, segregating and harassing them, with the hopes of driving them out.

As one of the first Black women to move into the dormitories, Ms. Whitby was a prime target. When she was away, officials conspired to illegally evict her, arguing that as a single occupant, she was no longer eligible for housing even though she had already moved in and paid rent.

The racism that Black residents at the shipyard dormitories like Ms. Whitby faced didn’t stop with those who managed the apartments. Black families also had reason to fear their white neighbors. Earlier that month, a white man had shot a Black child on dormitory grounds, allegedly because they had a disagreement over hot water.

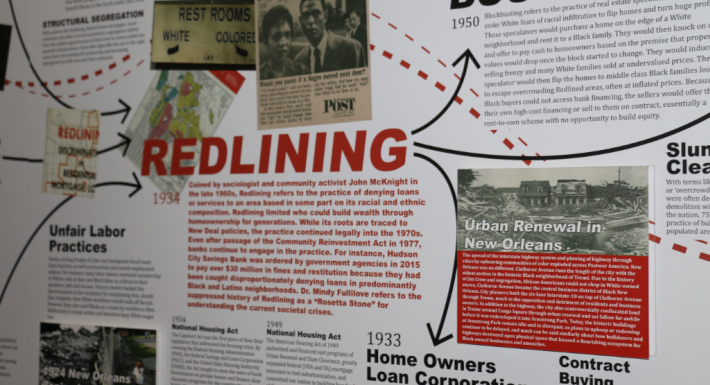

For people in Ms. Whitby’s situation, finding alternative safe housing was not easy. The real estate market was filled with racial housing covenants: contracts written into deeds forbidding future owners from selling to, renting to, or at times even letting Black people onto their property. As Ms. Whitby’s case shows, public housing wasn’t much better. The San Francisco Housing Authority, for instance, kept tightly segregated facilities and only allowed Black people to live in one low-income building.

The ACLU News archive, dating back to 1945, documents the various forms of legalized housing discrimination leveled at Black people in Northern California, and also charts severe backlash to progress, whenever it was made. It provides a snapshot of the ways that businesses, the state, and individuals partnered to exclude Black people from the accumulation of wealth through dispossession and the denial of their means to secure a home.

Read more at: https://www.aclunc.org/blog/exploring-aclu-news-archive-fight-against-housing-discrimination-california-story-progress-and?fbclid=IwAR39fe8s6G3u8I_1b3CYWNEshzZxo-9pGLhxci-mdSm0EwschiO7QDhoXN4