Author: Analisa Brewer

Exit Capitalism, Stage Left: Episode 3 Out Now

The third episode of Exit Capitalism, Stage Left is out now. This podcast is supported by The Maggie Phair Institute for Democracy and Human Rights. In this episode, I explore the concepts of mour... Read MoreMourning in a Capitalist, COVID, and Necropolitical World

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (the most English major source to cite, I know), mourning is (3.a.) “to feel or express sorrow, grief, or regret,” (4.a.) “to lament or grieve over a d... Read MoreExit Capitalism, Stage Left: Episode 2 Out Now

The second episode of Exit Capitalism, Stage Left is out now. This podcast is supported by The Maggie Phair Institute for Democracy and Human Rights. In this episode, special guest Matt Millholan... Read MoreCalifornia Housing Discrimination

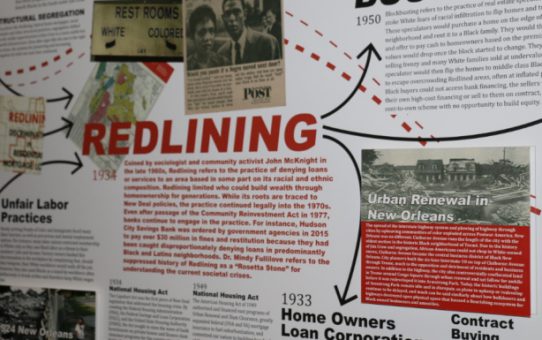

The ACLU News archive, dating back to 1945, documents the various forms of legalized housing discrimination leveled at Black people in Northern California, and also charts severe backlash to progres... Read MoreThe History of Capitalism and Human Rights

The History of Capitalism is the History of Exploitation. In the early modern period, capitalism and oppressive power structures like racism, sexism, ableism, and classism (just to list a few) formed ... Read MoreExit Capitalism, Stage Left: Episode 1

The Maggie Phair Institute for Democracy and Human Rights has put out its first podcast – Exit Capitalism, Stage Left, run by me, Manda Riggle, the new educator for the institute. This podcast e... Read MoreInterested in Learning About Socialism? Here’s a Reading List You Might Find Helpful

You’re interested in learning more about socialism and its history, but you aren’t sure where to begin. There’s just so much information out there, and some of it, particularly where... Read MoreThe Maggie Phair Institute Sits on Gabrielino-Tongva Land

“Under the crust of that portion of Earth called the United States of America—”from California . . . to the Gulf Stream waters”—are interred the bones, villages, fields, and sacred o... Read More- 3 of 4

- « Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next »